S22A

4UR Ranch, Creede, CO, USA

The USArray component of the NSF-funded EarthScope project ended its observational period in September 2021 and all remaining close-out tasks concluded in March 2022. Hundreds of seismic stations were transferred to other operators and continue to collect scientific observations. This USArray.org website is now in an archival state and will no longer be updated. To learn more about this project and the science it continues to enable, please view publications here: http://usarray.org/researchers/pubs and citations of the Transportable Array network DOI 10.7914/SN/TA.

To further advance geophysics support for the geophysics community, UNAVCO and IRIS are merging. The merged organization will be called EarthScope Consortium. As our science becomes more convergent, there is benefit to examining how we can support research and education as a single organization to conduct and advance cutting-edge geophysics. See our Joining Forces website for more information. The site earthscope.org will soon host the new EarthScope Consortium website.

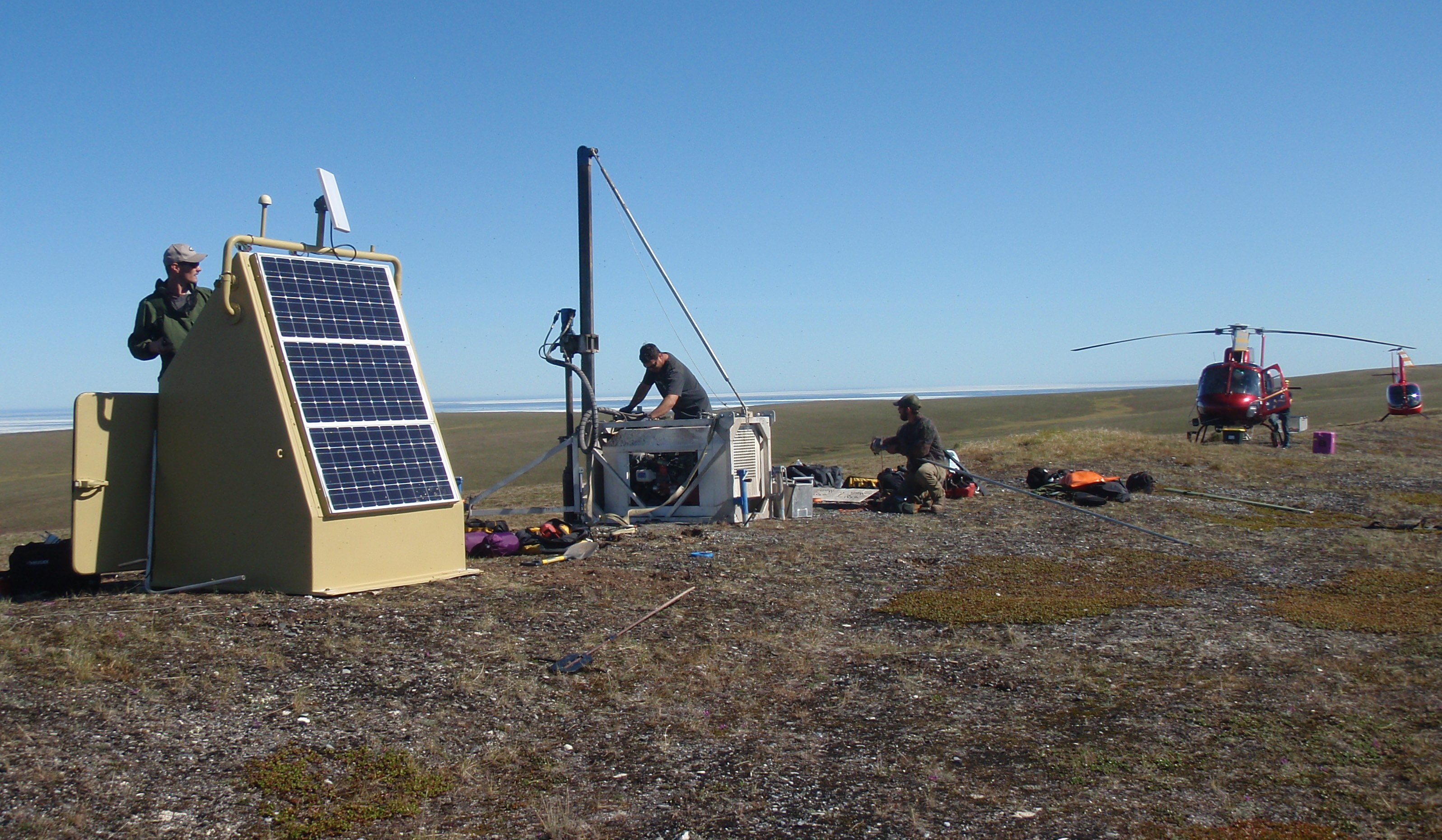

The ambitious 2016 Alaska Transportable Array deployment is in full swing with only 14 of the 72 new installations of seismic stations still to complete. Last year’s installations required nimble rescheduling around the over 5 million acres burned in 2015, including the Sockeye fire that reduced one brand new TA station to cinders. With the improved conditions this year, multiple field teams are pushing the grid of 268 uniform seismic stations steadily outward into more remote areas of the state accessible only by helicopter. Join the crew as they work through midnight sun and summer snowfall, curious wildlife, unexpected breakdowns, and the ever-present mosquitos.

Many of the stations in the Alaska Transportable Array deployment are in remote, helicopter only accessible locations. Getting to and from the sites can be highly dependent on weather and good visibility, requiring some flexibility in the already packed field season schedule. Here some low-lying clouds make for a tense trip to Q18K, but the skies open up for some incredible views later in the day.

With so much time spent in helicopters, the crew has been trained in Learn to Return safety procedures along with bear safety, first aid, and wilderness training. Jeremy Miner (right) exhibits some of the safety equipment of TA field work: a sturdy helicopter helmet and a full beard.

A helicopter slings the Silver Drill out after drilling the hole for station D23K in Nanushuk River, AK. The drills are specially designed for the Alaska Transportable Array to be light enough to transport in one load, yet still capable of drilling into several meters of bedrock.

Few stations are road-accessible but trucks are used where possible as seen here at station M23K.

K24K The drill stands at station K24K with a steel casing (black cylinder) locked and loaded and ready to go into the ground. The casings are surprisingly fragile since they are made out of a lighter grade of steel to save on weight.

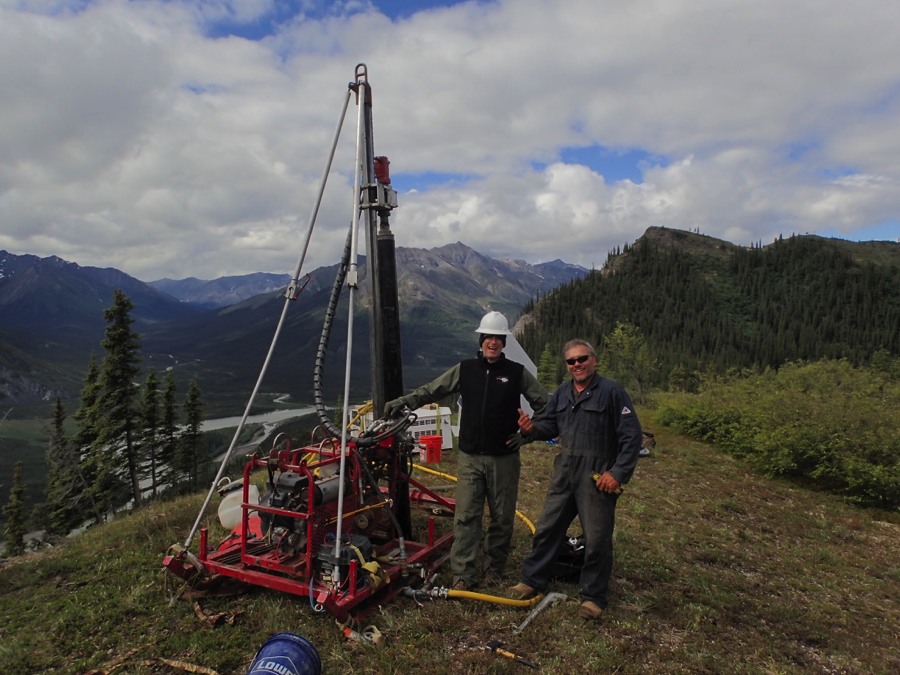

The drills used in the Alaska TA fieldwork are specially designed to be as light as possible while still able to drill a cased hole through meters of bedrock, mud, cobbles, sand, clay, and permafrost. With such a stripped down drill, experience is a must in the drillers in order to navigate a difficult hole without applying too much power and damaging the drill. The drillers go through additional training with Mike Lundgren (right) who designed the drills.

Hammer drilling can be messy business depending on the ground type as can be seen here at station R16K. The drillers have to navigate the steel casings through 2-3 meters of mud, sand, clay, permafrost, cobbles, or, preferably bedrock.

Jeff Rezin operates the pump to push grout down the newly drilled hole. Oftentimes the crews will split up, with the construction team working ahead to drill and prep the boreholes at each site and the installation team following up to place the sensor down the hole after the grout has dried and hook up the rest of the station components.

Ryan Bierma works on setting up the communication systems on station C23K. The station huts are large enough to uncomfortably accommodate several technicians along with the equipment, and have been used by the crew to shelter from inclement weather, bugs, and curious bears during station visits.

The unofficial state bird, the mosquito, can be seen all over the state in the summertime and are big fans of the field teams. Station specialists have utilized all kinds of methods for handling the prolific insects including head nets, repellents from natural to caustic, and bug-proof clothing.

Other wildlife sightings this season include bears, muskox, caribou, and this curious fox at Kavik River Camp.

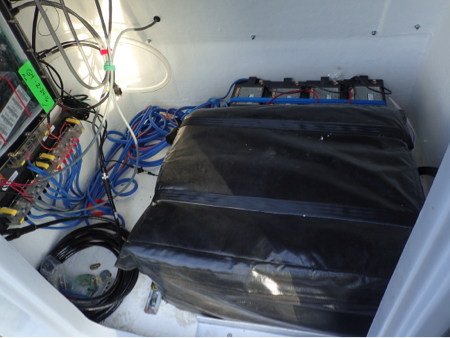

Jason Theis puts the final tape on the door of station P33M. After complications with the power system were traced back to excess moisture in the first deployed stations, changes were made to the installation procedure to prioritize a dry, ventilated hut. The lithium batteries are now packed within a separate waterproof bag (below) inside the hut, requiring additional time to assemble but ensuring protection from any condensation.

Station sites may sometimes look untidy during construction (above), but by the time a station is finished all equipment is neatly tucked away, and all tools, unused materials, and trash are transported back to the staging area (below).

When all goes well with weather and equipment, a full station can installed in a single day. This is largely due to the uniform nature of the stations as well as the months of winter preparation for assembling the station kits, pre-programming equipment, and re-checking checklists. Each station is shipped as assembled as possible to make field operations efficient in both time and cost.

Problems often arise that require troubleshooting to get a station fully operational. A return visit can be extremely expensive so station specialists need to be able to work through electrical, mechanical, and networking problems in the field as needed to resolve all errors before leaving.

Doug Bloomquist makes sure all systems are functioning as expected at station P17K. Since the huts are already physically assembled as much as possible before being deposited on site, much of the installation time is often spent getting communication up and running rather than actual station construction. The real-time feeds can be a pain to set up, but being able to check in with the Array Network Facility and confirm data is flowing can be a major relief for the crew before they depart a site.

Snow accumulates on station C24K during summer solstice, the first official day of summer. Field work is planned with as much flexibility as possible since conditions can change drastically day-to-day.

Here work at Q17K starts out in bright sunshine (above) but is later socked in with fog (below) making the return journey more difficult. All field teams carry satellite radios to communicate and arrange alternative plans when weather starts changing or other delays are encountered due to equipment and site conditions.

Field work during Alaskan summers can be pleasant, and it is hard to quit at the end of the day when the sun is still up and bright.

The crews work long days but know that they can't burn out during their multiple-week deployments, particularly when they only get a handful of days at home before heading out again.

The field teams spend a significant amount of time together, through everything from frenetic-paced work to tedious hours while waiting for weather to clear on site. Stress is high when success depends on many factors out of their control, so light-hearted pranks and a positive attitude are key to survival in the Alaskan wilderness.

Photos above were taken by Maria Sanders and Jeremy Miner. To learn more about the Alaska Transportable Array project, please follow this link.